A new study published in the journal Nature Communications describes a breast cancer DNA “methylome,” a new way of looking not just at the DNA sequence, but also how it may have been altered by epigenetics.

A new study published in the journal Nature Communications describes a breast cancer DNA “methylome,” a new way of looking not just at the DNA sequence, but also how it may have been altered by epigenetics.

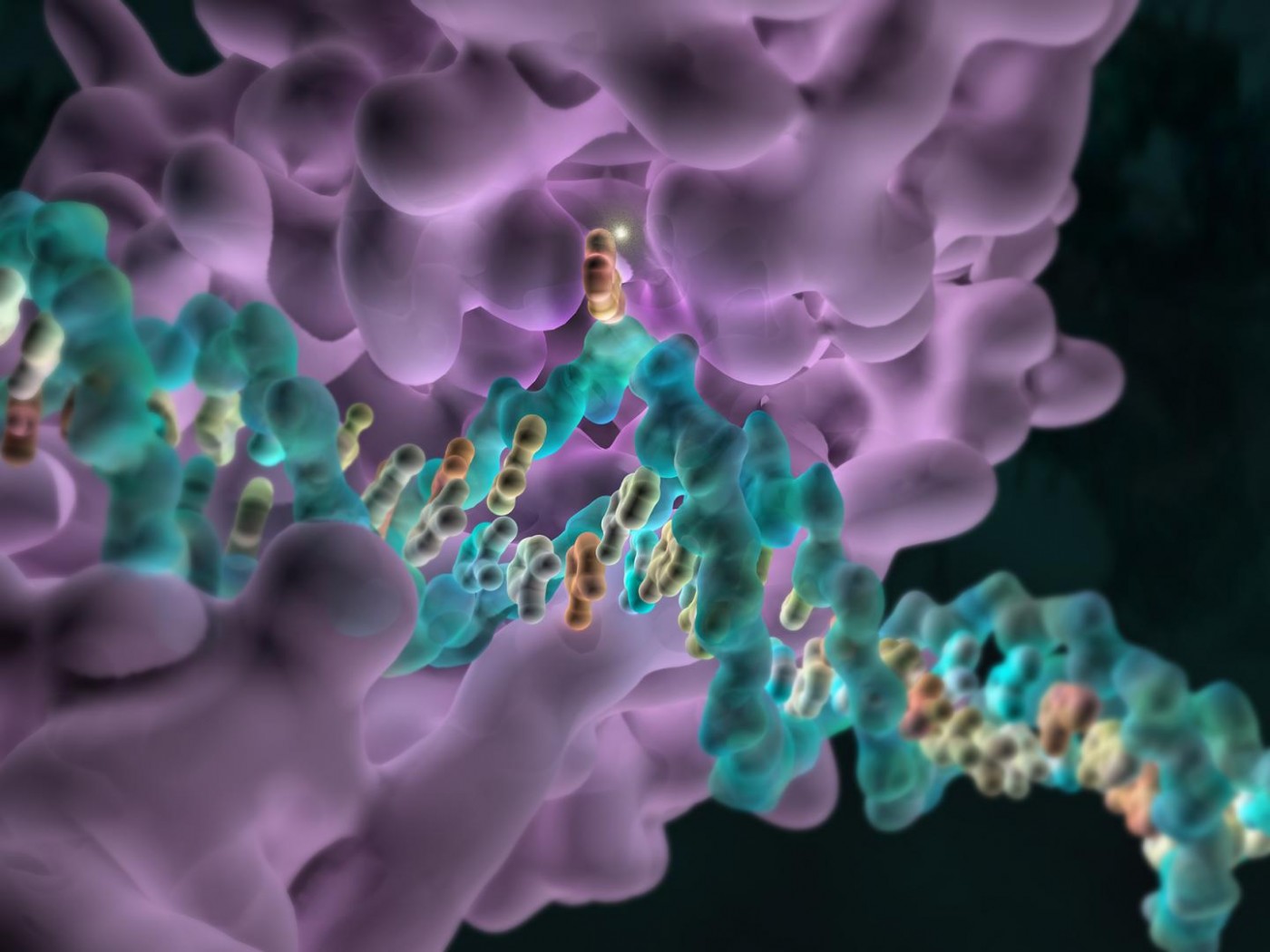

Epigenetics refers to inherited changes in genes that do not involve changes to the DNA sequence. This could imply a process known as “methylation” which occurs when a chemical group called a methyl is added to the DNA sequence at different sites. Epigenetic changes occur often, and can be influenced by different factors including age, the environment, nutrition, and diseases.

In this study, researchers identified specific methylation patterns in breast cancer cells taken via biopsy from triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) patients that indicated whether the cancer was more or less likely to worsen or respond to treatment.

TNBC accounts for 15 to 20% of all breast cancers and lacks any one of three specific markers: receptors for estrogen, progesterone or HER2. Current treatments target these specific cellular receptors, so unfortunately this type of tumor has the worst outcome compared to other breast cancers. Some people with TNBC will die within 3-5 years after diagnosis while others remain free of cancer for eight years or more. It is not currently possible to predict which of the two breast cancer categories a patient will fall into.

Professor Susan Clark, Dr Clare Stirzaker and Dr Elena Zotenko, both from Sydney’s Garvan Institute of Medical Research, analyzed methylation patterns to create a methylome for TNBC. They used breast cancer samples from TNBC patients and matched normal samples from healthy donors, identifying cancer-specific changes in DNA methylation.

According to Dr. Clark “This is the first study to investigate the methylome of triple negative breast cancer — and its association with disease outcome. There is a clear need for better informed disease management. In the absence of robust prognostic tools, too many women are being over-treated.”

[adrotate group=”3″]

Pathologist Dr Glenn Francis, who analyzed the tissue samples for the study, added, “The information we have at the moment is based on statistics and probability, and we are forced to treat triple negative breast cancer patients as a group, even though we know that they are not a uniform population. By stratifying tumors epigenetically, this study should enable us to track selected groups of patients over time, monitoring how they respond to different treatments. From a purely practical standpoint, it’s useful that reliable results were obtained from formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded tissue — as this is the material routinely used for diagnosis.”

“We were very pleased to find a way to interrogate this archival DNA – a valuable resource because methylation patterns can be correlated with patient outcomes,” said Dr Stirzaker. “Developing the methylation sequencing methodology allowed us to answer a new question.”

With these promising initial results, the investigators plan to continue their work in a larger group of triple-negative breast cancer patients.