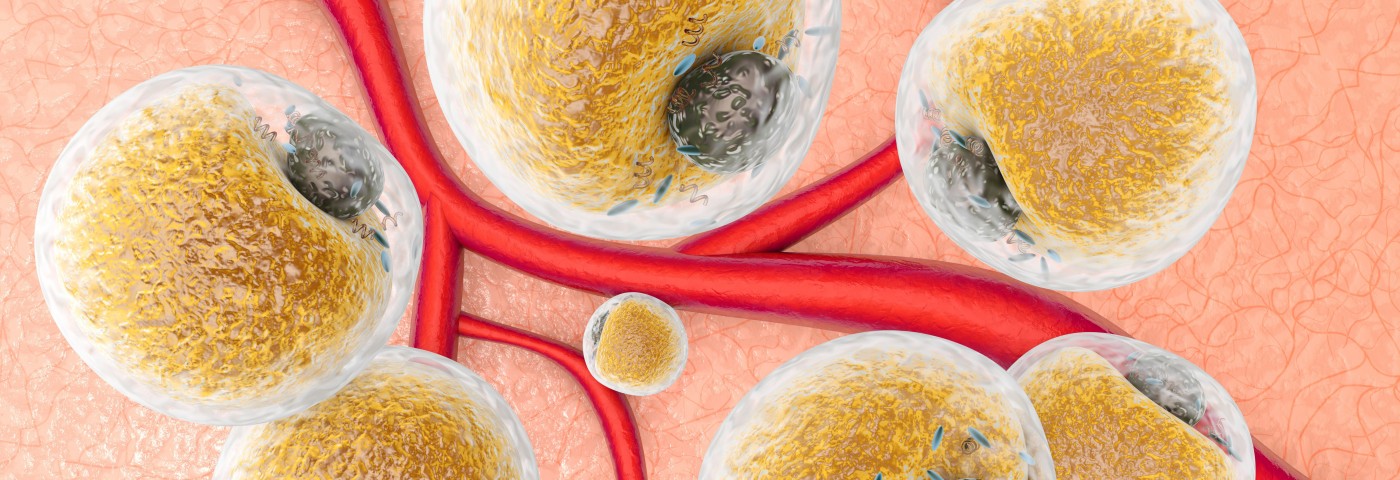

Researchers at the Spanish Institute for Research in Biomedicine in Barcelona have discovered that breast cancer cells need to take up fat from their environment in order to grow. The finding provides a novel way to slow or possibly block tumor growth, raising hopes of new and potentially less toxic cancer treatments.

Because they are fast-growing, tumors need plenty of energy. Earlier studies have shown that cancer cells take up glucose from the extracellular environment, and reprogram their cellular machinery to produce more fat. The study, “FoxA and LIPG endothelial lipase control the uptake of extracellular lipids for breast cancer growth,” published in the journal Nature Communications, shows that this is not enough to cover breast cancer cells’ energy needs.

The process of importing fats — or lipids — into cells is the work of an enzyme called LIPG. When analyzing two groups of around 500 samples each from breast cancer patients, the research team found that nearly 85 percent of the samples had unusually high levels of the protein, particularly when comparing the levels to normal breast tissue.

Complementing their work with animal experiments, researchers also found the genes controlling the expression of the LIPG protein, FOXA1 and FOXA2.

When the team removed the LIPG protein from the cells, their growth is slowed. Noting the same result when blocking FOXA, the researchers also evaluated the types of fats these cells processed when LIPG was absent. They noted that without the protein the cells could metabolize fewer fat types, again suggesting that fat import was crucial for cellular growth.

“This new knowledge related to metabolism could be the Achilles heel of breast cancer,” Roger Gomis, one of two co-senior authors of the study, said in a press release.

The researchers now plan to develop LIPG blockers, and are seeking international partners for the task. They note that LIPG is an attractive target, with several characteristics making drug development easier.

“What is promising about this new therapeutic target is that LIPG function does not appear to be indispensable for life, so its inhibition may have fewer side effects than other treatments,” said Felipe Slebe, the study’s first author.

“Because LIPG is a membrane protein, it is potentially easier to design a pharmacological agent to block its activity,” added Joan J. Guinovart, the institute’s director and a professor at the University of Barcelona.