Scientists with Cancer Research UK at Kings College London have developed new imaging techniques that can identify with greater accuracy breast cancer patients that

Scientists with Cancer Research UK at Kings College London have developed new imaging techniques that can identify with greater accuracy breast cancer patients that  might respond to human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) targeted treatments. More than 53,600 women are diagnosed with breast cancer every year in the UK. Approximately one in five of the more than 53,600 women diagnosed with breast cancer annually in the UK have tumors classified as HER2 positive.

might respond to human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) targeted treatments. More than 53,600 women are diagnosed with breast cancer every year in the UK. Approximately one in five of the more than 53,600 women diagnosed with breast cancer annually in the UK have tumors classified as HER2 positive.

HER2 is one of a family of four similar biochemical molecules whose function is to help cells grow when the conditions are right. When they’re not right and cells don’t make enough of these molecules, the shortfall can result in neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease. Conversely, if cells make an excess of HER molecules, cancers can develop.

In response to external signals, HER molecules will stick together in pairs, called dimers, causing their shape to change, which in turn activates a range of cellular processes, causing the cell to divide. However, according to the Kings College London researchers and their colleagues, different HER proteins can also pair up with each other, producing different effects on a cell. Studying these pairings can enhance understanding of how cancer cells might be growing.

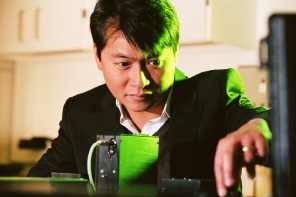

The investigative team, led by Richard Dimbleby, professor of cancer research at King’s College London, and and Tony Ng, professor at King’s College London and professor of molecular oncology at UCL-Cancer Institute, University College London, have reported their discoveries in a research paper published in the journal Oncotarget.

The investigative team, led by Richard Dimbleby, professor of cancer research at King’s College London, and and Tony Ng, professor at King’s College London and professor of molecular oncology at UCL-Cancer Institute, University College London, have reported their discoveries in a research paper published in the journal Oncotarget.

The study, “HER2-HER3 dimer quantification by FLIM-FRET predicts breast cancer metastatic relapse independently of HER2 IHC status,“ notes that overexpression of HER2 is an important prognostic marker, and the only predictive biomarker of response to HER2-targeted therapies in invasive breast cancer.

The authors observe that HER2-HER3 dimer has been shown to drive proliferation and tumor progression, and targeting this dimer with the breast cancer drug Perjeta (pertuzumab) alongside chemotherapy and Herceptin (trastuzumab), has shown significant clinical utility.

The specific purpose of the study was to accurately quantify HER2-HER3 dimerisation in formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) breast cancer tissue as a novel prognostic biomarker.

The investigators conclude that future applications of their technique might include highlighting a group of patients who do not overexpress HER2 protein but are nevertheless dependent on the HER2-HER3 heterodimer as a driver of proliferation, and this assay technique could, if validated in a group of patients treated with, for instance, Perjeta, be used as a biomarker to predict for response to such targeted therapies.

The team at Kings College London, in collaboration with scientists at the CRUK/MRC Oxford Institute for Radiation Oncology, used a combination of two techniques called fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) and Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) — collectively called FLIM/FRET — to confirm if key proteins have joined together. FLIM/FRET can be used to accurately measure the distance between two protein molecules.

In the example of this investigation, researchers measured the distance between HER2 and HER3 proteins in breast cancer cells from patients, and deduced that patients whose imaging results show bonding these proteins together could benefit from HER2 targeted treatment, regardless of whether their tumor has high HER2 levels.

HER2 is a protein that can cause cancer cells to grow. HER2-positive breast cancer cells have high levels of the protein, and can be targeted with drugs that block its effects and stop the cancer from growing. Drugs being used now include Herceptin and Tykerb. Patients who could benefit from these drugs are identified by testing their cancer cells to see if they show high levels of the HER2 protein.

This imaging technique, carried out in tumor cells, could pick up additional patients in the future who would respond well to HER2-targeting drugs, and could also confirm which patients may not be suitable for these treatments.

“This imaging technique could help us pick up patients who might benefit from these drugs but have previously been overlooked,” Tony Ng said in a press release. “Using this test, we should be able to predict which drugs won’t work in patients and avoid prescribing unnecessary treatments, putting the drugs that we’ve got to better use.

“The next step is to run clinical trials to see if this test could help patients. We hope that one day it could not only improve treatment for breast cancer but also for other cancers including bowel and lung cancer,” he said.

Nell Barrie, senior science information manager at Cancer Research UK, said there are more than 50,000 new cases of breast cancer each year in the UK, but due to advances in research, more people are surviving the disease.

“This research could eventually give doctors another way to personalize treatment so that patients receive the drugs that are most likely to help them,” Barrie said.