A new method using small particles loaded with chemotherapy drugs is a viable approach to target breast cancer cells that have spread to the bones, according to a report that appeared in the journal Cancer Research.

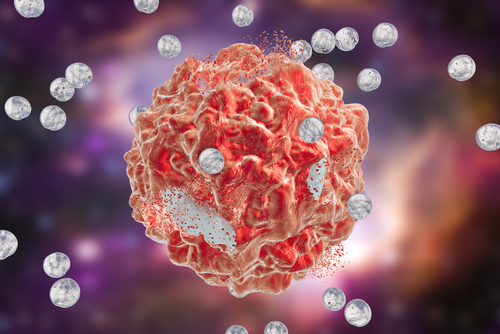

The strategy, developed by a research team at Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM) in St. Louis, Missouri, combines a nanoparticle-based drug delivery method with a surface molecule called integrin β3. The integrin enables the small particles to get inside the bones and deliver the chemotherapy drug directly to the cancer cells.

In the study, titled “Bone-induced expression of integrin β3 enables targeted nanotherapy of breast cancer metastases,” researchers provided preclinical data showing that the new approach kills cancer cells while reducing treatment-related toxicity in healthy bone tissues.

“For women with breast cancer that has spread, 70 percent of those patients develop metastasis to the bone,” Katherine N. Weilbaecher, MD, professor of medicine at WUSM and senior author of the study, said in a university news release, written by Julia Evangelou Strait.

“Bone metastases destroy the bone, causing fractures and pain. If the tumors reach the spine, it can cause paralysis. There is no cure once breast cancer reaches the bone, so there is a tremendous need to develop new therapies for these patients,” Weilbaecher said.

Integrin β3 is a surface molecule that helps cells move throughout the body. In cancer, high levels of this protein are linked to an increased ability to migrate, invade, and survive in different microenvironments.

Using mice with metastatic breast cancer, researchers found that high levels of integrin β3 were seen only in cancer cells that had spread to the bone. Cancer cells in the breast or other metastatic sites, including the liver or lung, had low levels of this molecule.

To assess whether the bone metastatic process could be targeted using this molecule, researchers developed a nanoparticle containing the chemotherapy Taxotere (docetaxel). These nanoparticles were covered with small molecules that bound specifically to integrin β3, so the chemotherapy drug was released only when the nanoparticles were in direct contact with integrin β3-positive cancer cells.

Testing the drug in mice, the team confirmed that the nanoparticles were able to enter the bone and to reduce the tumor, which suggested the drug was effectively killing cancer cells.

“When we gave these nanoparticles to mice that had metastases, the treatment dramatically reduced the bone tumors,” Weilbaecher said. “If we can deliver the chemo directly into the tumor cells with these nanoparticles that are using the same adhesive molecules that the cancer cell uses, then we are killing the tumor and sparing healthy cells.”

The approach also reduced bone destruction and bone fractures, the team found. This was likely because integrin β3 is also found in osteoclasts, the cells that break down bone. Inhibiting their function could reduce bone damage in patients with bone metastasis.

The nanoparticles also reduced the amount of chemotherapy needed to treat the mice.