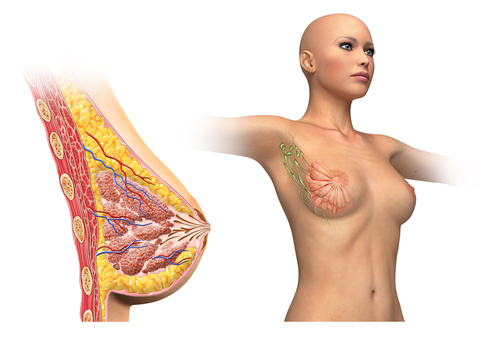

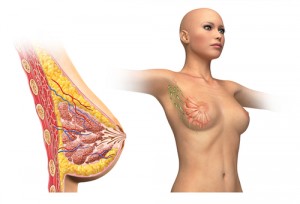

Researchers in the laboratory of Alexander S. Popel, PhD, at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine are finding ways of preventing breast cancer metastasis. After discovering breast cancer cells can enable their own spread by affecting cells of the lymphatic vessels, Dr. Popel’s team conducted in vitro and in vivo experiments to put a halt to this phenomenon.

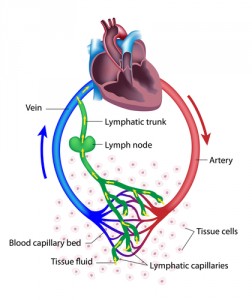

“Conventionally, lymphatic vessels are regarded mainly as passive conduits through which tumor cells spread from the primary tumor and eventually metastasize,” said Dr. Popel in a news release from Johns Hopkins Medicine. “However, we now know that lymphatic vessels enable metastasis, and other studies also show that they play an important role in whether or not immune cells recognize and attack cancer cells.”

It all starts with breast cancer cells releasing signaling molecules that affect lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) in the lungs and lymph nodes. In response to the signals, LECs produce CCL5 and VEGF, proteins that attract tumor cells and increase the number and porosity of blood vessels, respectively. This enables breast cancer metastasis. “It was surprising to find that LECs can play such an active and significant role in tumor spread,” commented Dr. Popel.

These findings were published in Nature Communications under the title, “Breast Cancer Cells Condition Lymphatic Endothelial Cells Within Pre-Metastatic Niches to Promote Metastasis,” by lead author Esak Lee and co-authors Niranjan Pandey from the Biomedical Engineering Department and Elana Fertig, Kideok Jin, and Saraswati Sukumar from the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center. Together, the team conducted studies in cell culture to find the root mechanism for CCL5 and VEGF expression by LECs.

Breast cancer cells were bathed in a nutrient-rich medium, which was then analyzed for expression of interleukin-6 (IL6), a signaling molecule. The medium was found to be enriched in IL6, which was involved in a signaling cascade with the proteins Stat3, HIF-1α, c-Jun, and ATF-2 and eventually resulted in inducing VEGF and CCL5 expression.

[adrotate group=”3″]

Probing further, the researchers injected the cancer cell-condition medium into tumor-bearing mice. Injected mice had higher levels of CCL5 that lasted for several weeks. Nine of the ten mice developed metastases within five weeks. Dr. Popel noted that “IL6-secreting tumors could be laying the groundwork for metastasis much earlier than surgery occurs in a patient. To prevent metastatic sites from taking root, we could administer drugs that block IL6 before surgery.”

Probing further, the researchers injected the cancer cell-condition medium into tumor-bearing mice. Injected mice had higher levels of CCL5 that lasted for several weeks. Nine of the ten mice developed metastases within five weeks. Dr. Popel noted that “IL6-secreting tumors could be laying the groundwork for metastasis much earlier than surgery occurs in a patient. To prevent metastatic sites from taking root, we could administer drugs that block IL6 before surgery.”

The team delved into possible treatments both in cell culture and in mice. They used an approved HIV drug known as maraviroc and an anti-VEGF antibody. Mice that had been injected with IL6-rich cancer cell-conditioned medium and then both maraviroc and anti-VEGF antibody had fewer metastases: only two of ten developed metastases. It is thought that maraviroc, which blocks the actions of CCL5, could be delivered with chemotherapy after surgery to remove a tumor to prevent leftover tumor cells from metastasizing to a new niche in the body.

So far, Dr. Popel’s team has not addressed when or how to remove lymph nodes, which is a standard part of breast cancer treatment, but there are hopes to explore further. This initial study was funded by the National Institute’s of Health’s National Cancer Institute and Safeway Foundation for Breast Cancer.

If results continue to show potential for breast cancer treatment, the road to clinical trials in humans may be relatively short. Maraviroc, an anti-retroviral drug for HIV, has already been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Studies have demonstrated its safety with long term, oral use. Further data may enable its approval to prevent breast cancer metastases.