The human body may be able to fight breast cancer naturally, as suggested by new research conducted at the Scripps Research Institute that found evidence of antibody production in healthy seniors.

The human body may be able to fight breast cancer naturally, as suggested by new research conducted at the Scripps Research Institute that found evidence of antibody production in healthy seniors.

Without knowing it, these patients’ immune systems fought cancer, naturally creating antibodies that may help design novel cancer therapies.

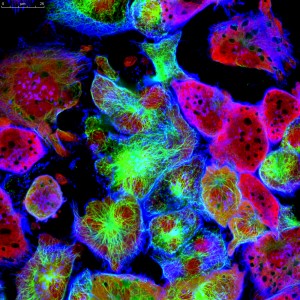

Investigators at the Scripps Research Institute began screening the DNA in blood samples from healthy people older than 80 years, designated as “wellderly,” to understand what enabled them to live a long and healthy life. During the research, the team found that these patients produced antibodies connected to triple negative breast cancer, for which there is no targeted therapy.

When blood samples of senior patients who had never suffered from cancer were analyzed, the team discovered evidence of past victories against cancer. “I thought that the human immune system is really our best defense against cancer,” said in a press release study author Brunhilde “Brunie” Felding. “The wellderly have had a healthy long life. My question was: Do these people have antibodies we should look into?”

Antibodies against a particular protein, present in an aggressive triple negative breast cancer cells, were found in wellderly’s blood samples. Felding explained that the cancer cell protein integrated a signaling route, and could act as a “driving pathway in this aggressive cancer, an indicator of where to look for therapeutic targets.”

[adrotate group=”3″]

The investigator believes that these women’s own immune systems fought breast cancer during their lives without raising any visible signs, since their bodies were confronted with a pathogen and naturally created a successful antibody able to neutralize it. Despite the fact that the pathogen was already gone, the antibodies continue to exist in the patients’ immune memory, able to be reused in case of a resurgence.

“If there were aberrant cells at some point in a person’s body, but a noticeable cancer never developed, the immune system likely coped with those stray cells, and the antibody memory would still be there years later,” explained Felding. “Finding an effective therapy for these types of breast [triple negative tumors for which there is no targeted therapy] is one of our main goals in cancer research.”

“Overall, the concept of exploring the immune system is very promising. The fact that the wellderly blood donors are in their 80s means that their immune memories are very rich,” added Felding. The research was supported by the California Breast Cancer Research Program, and a broader study including the same patients is already being conducted by professor Eric Topol at the Scripps Research Institute.