Researchers have identified a biomarker that may help predict which breast cancer patients are likely to respond to microtubule-stabilizing drugs like Taxol (paclitaxel).

The protein, called Mena, is involved in a newly discovered mechanism through which highly metastatic cancer cells become resistant to such drugs, and blocking it may be a promising approach to improve their response to Taxol.

The study, “Mena confers resistance to Paclitaxel in triple-negative breast cancer,” was published in Molecular Cancer Therapeutics.

“Drugs that target that pathway restore paclitaxel sensitivity to cells expressing Mena,” Frank Gertler, an MIT professor of biology and member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, said in a press release. “The study also suggests that during the course of treatment it might be worth monitoring the level of Mena. If the levels begin to increase, it might suggest that switching to another type of therapy could be useful.”

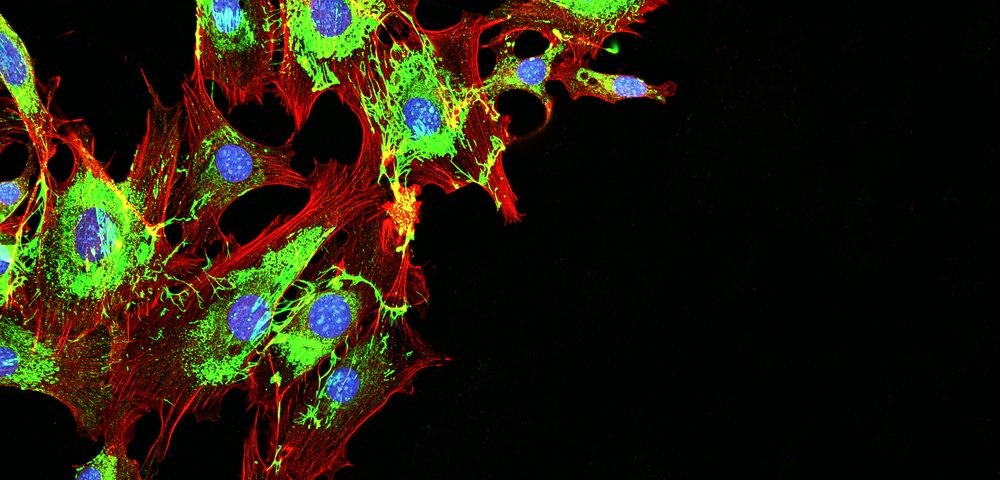

The Mena protein is known to interact with the cell’s cytoskeleton to help the cells become mobile. Mena, and its isoform Mena invasive, or MenaINV, are highly expressed in various types of cancers, and are established drivers of metastasis.

In a prior study, Gerter and his team found that high levels of these proteins in breast cancer patients were associated with increased metastasis and lower survival rates.

Now, the researchers wondered whether Mena and MenaINV could affect tumor cell responses to chemotherapy, and whether chemotherapy could, in turn, alter the expression of such proteins.

Although the number of targeted therapies for breast cancer continues to rise, chemotherapy remains the standard of care for patients with the aggressive triple-negative breast cancer, and patients usually relapse within six to 10 months. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms through which cancer cells become resistant to chemotherapy is crucial.

Testing a number of chemotherapies in triple-negative breast cancer cells with different levels of Mena, investigators found that Mena levels did not affect the cell’s sensitivity to chemotherapies like Adriamycin (doxorubicin) or Platinol (cisplatin), but did affect their sensitivity to Taxol. Those with higher levels of this protein were the most resistant to Taxol.

Similar results were obtained when mice with metastatic triple-negative breast tumors were treated with Taxol; those with the highest levels of Mena showed the worst response to treatment.

Taxol is a chemotherapy agent that works by stabilizing the cell’s microtubules (which are part of the cell cytoskeleton), halting cell proliferation, and leading to cancer cell death. But the study revealed that cells with high levels of Mena had more dynamic microtubules, which was likely involved in the cell’s resistance to the drug.

The researchers knew that Taxol treatment increased the levels of ERK1, a protein also known to interact with microtubules, which counteracts the Taxol-derived microtubule stabilization. They assessed whether blocking this protein could enhance the response to Taxol in cells with high levels of Mena.

Indeed, they found that combining Taxol with an ERK inhibitor increased cancer cell death when compared to Taxol treatment alone, and clinical trials are now underway to test this combination in breast cancer patients.

“Our work would suggest that for a certain subset of patients that have high levels of Mena, that could be an efficient combination to try,” said Madeleine Oudin, a Koch Institute postdoc, and the paper’s lead author.

In addition, the researchers believe that levels of the Mena protein may help doctors choose treatments for breast cancer patients, sparring them chemotherapy that is likely to be less effective.