The localized activation of an anti-cancer medicine in tumor cells, through an innovative internal light source, significantly reduced metastatic tumor growth, according to a new study using mice.

This response was observed in both aggressive metastatic breast cancer and multiple myeloma, a type of cancer of white blood cells.

The study, “Radionuclides transform chemotherapeutics into phototherapeutics for precise treatment of disseminated cancer,” was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Phototherapy has been shown to be a precise and safe strategy against cancer. It involves the activation of a light-sensitive molecule or drug through exposure to certain types of light.

However, its effectiveness is limited to cancer in the skin or in areas accessible by an endoscope due to the low penetration power of light in tissues.

Cherenkov radiation, a specific light emitted by radioactive molecules, has been used in traditional cancer-imaging techniques, such as positron emission tomography (PET), to locate metastatic tumors.

Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is a radiolabeled sugar molecule commonly used in PET scans, due to the production of Cherenkov radiation. Many tumors take up high amounts of FDG to support their rapid growth, making them light up on a PET scan, no matter where they are in the body.

Previous work from a team of researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis showed that Cherenkov light (through FDG) could be used as an internal light source to activate light-sensitive molecules in deep tissues.

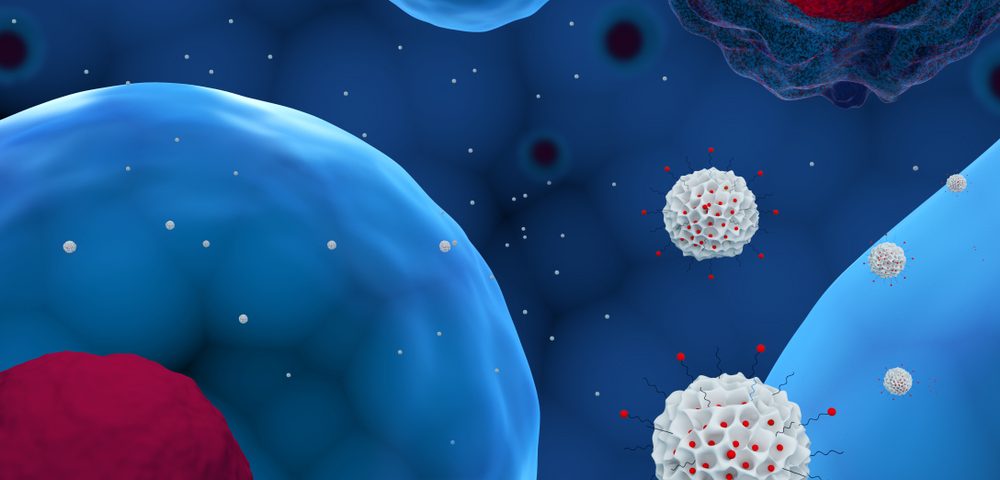

Now, the team developed a strategy to co-localize a light-sensitive drug with the source of Cherenkov light in tumors.

Titanocene is a chemotherapeutic drug, so far with poor therapeutic outcomes in clinical trials. But when exposed to low-intensity light, it produces reactive particles that are toxic to cells.

So, researchers loaded titanocene into nanoparticles designed to target specifically each type of cancer and deliver the drug inside cancer cells. The co-localized light emitted by FDG induced the release of free radicals from titanocene, killing the cancer cells.

This combination strategy significantly inhibited cancer growth in mice with aggressive metastatic breast cancer, compared to mice with no treatment or treated with only titanocene or FDG.

“Our study shows that this phototherapeutic technology is particularly suited to attacking small tumors that spread to different parts of the body,” Samuel Achilefu, PhD, the study’s senior author, said in a press release.

Some clusters of tumor cells did not respond to therapy. But the slow growth and the focal localization of these resistant cells “suggests that this therapeutic method can transform metastatic cancer into a surgical disease,” the researchers wrote.

“This is an opportunity to learn because it’s similar to what is seen in patients — some of the cells become dormant but don’t die after treatment,” Achilefu added.

“Future studies will explore different models and establish the mechanism of therapy resistance,” the team noted.

In mice with multiple myeloma, the combination therapy showed significant reduction of cancer growth and longer survival, although some cells also were resistant to treatment.

Scientists believe the toxic effects of this therapy are minimal compared to standard radiation and chemotherapy, since both the light and light-sensitive drug are targeted to the tumor. In addition, neither appears to be toxic when given alone.

Research also shows that the body eliminates titanocene and FDG through different organs, minimizing organ damage.

Achilefu and his team are now “interested in exploring whether this is something a patient in remission could take once a year for prevention.”

“The toxicity appears to be low, so we imagine an outpatient procedure that could involve zapping any cancerous cells, making cancer a chronic condition that could be controlled long-term,” he said.