The American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) changed the guidelines that determine which breast cancers are considered HER2-positive in 2013. According to a recent study from the Mayo Clinic, those changes have doubled the number of patients being diagnosed with HER-2 positive breast cancer.

The study, “Change in Pattern of HER2 Fluorescent in Situ Hybridization (FISH) Results in Breast Cancers Submitted for FISH Testing: Experience of a Reference Laboratory Using US Food and Drug Administration Criteria and American Society of Clinical Oncology and College of American Pathologists Guidelines,” was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“The new guidelines were established to reduce the number of equivocal cases, where HER2 status is uncertain, but we found that they did just the opposite,” Robert Jenkins, MD, PhD, the Ting Tsung and Wei Fong Chao professor of individualized medicine research and professor of laboratory medicine and pathology at Mayo Clinic, and the study’s senior author, said in a press release. “The number of equivocal cases went up, resulting in additional testing and a much larger number of women with cancers ultimately labeled as HER2-positive.”

HER2-positive breast cancers, characterized by high levels of the HER2 protein or by the presence of extra copies of the HER2 gene, tend to be more aggressive and to spread at a faster pace than other breast cancers. Understanding whether a newly diagnosed patient is HER2-positive is important because HER2-positive breast cancer can be treated with inhibitors of the HER2 pathway, such as Herceptin (trastuzumab), Tykerb (iapatinib), or Perjeta (pertuzumab).

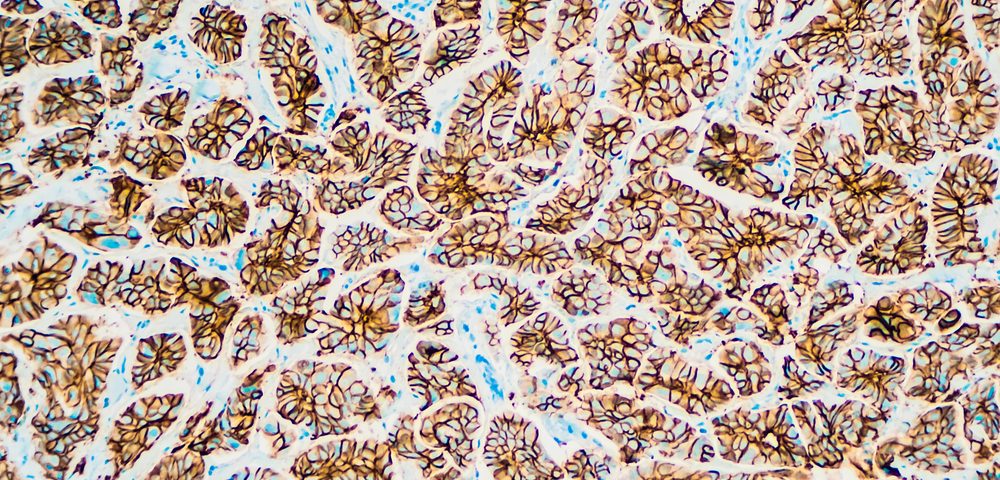

HER2 testing consists of two methods: immunofluorescence is used to detect the levels of HER2 protein within the cells, and fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) measures the number of copies of the HER2 gene that each cell possess.

The guidelines that determined which cancers were HER2-positive based on the results of these tests, determining patient’s eligibility for HER2-directed therapies, were first approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1998. But ASCO/CAP published a new set of guidelines (AC2007) in 2007, which were later updated to change the cut-off for equivocal and positive cases in 2013 (AC2013). The intent of the updated guidelines is to minimize false-positive and false-negative results.

To investigate the impact of the AC2013 guidelines in the number of HER2-positive breast cancers, the researchers examined FISH results from 2,851 patients and compared the prevalence of HER2-positive breast cancers using the three guidelines.

The team found that 13.1 percent of patients were HER2-positive according to the FDA criteria, and 11 percent according to AS2007, but this number nearly doubled to 23.6 percent when AC2013 criteria were used. This is important because the additional 10-15 percent that are now diagnosed as HER2-positive did not participate in clinical trials for HER2-directed therapies, and thus it is unclear whether these patients actually benefit from such therapies.

“Women who receive false positive results are not only exposed to the risks of HER2-directed therapies, but they also miss out on the treatments that could be effective against their cancer. That is counter to the goal of personalized medicine, which is to give the right drug to the right patient at the right time,” said Jenkins. “Given the medical, financial and psychosocial aspects of these targeted therapies, it is prudent that we prospectively identify the most optimal candidates for treatment.”