Most U.S. studies into the genetics of breast cancer were conducted in women of European ancestry, so it remains to be determined why African-American women are more likely to be diagnosed at younger ages, have more aggressive types of the disease, and die of breast cancer at higher rates than their white counterparts.

To address this gap, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis researchers are designing a large study in African-American women with breast cancer to understand if their genetic risk is due to the same induced genetic mutations affecting white women.

“We’ve had a revolution in genetic testing over the past 10 years,” the study’s senior investigator, Laura Jean Bierut, MD, the Alumni Endowed Professor of Psychiatry, said in a news release. “We’ve been able to identify many gene variants that contribute to a variety of cancers, including breast cancer. But as you examine the data, you realize most of these studies have been done in populations of European ancestry and that we don’t understand very much about the genetic causes of cancer in other populations, particularly in African-American women.”

African-Americans are nearly twice as likely as white women to be diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer, a more aggressive and harder-to-treat subtype, according to the National Cancer Institute, and they’re more likely to die of their cancer.

“Better understanding of the genetics of the disease in African-American women could be very helpful in earlier diagnosis, prevention and treatment,” said Foluso Ademuyiwa, MD, a co-investigator and assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Medical Oncology.

The study will enroll African-American women living in St. Louis who had breast cancer, regardless of when the disease was diagnosed. Participants will also be asked to provide two saliva samples, and to answer brief surveys about breast cancer risk factors, such as family history, number of children, and hormonal treatments.

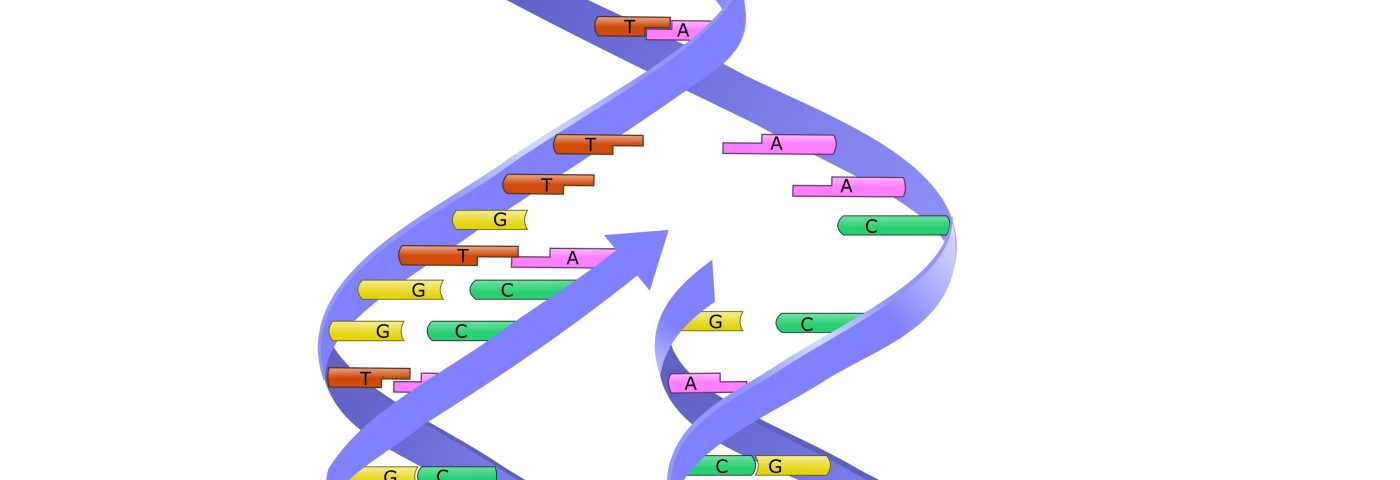

The researchers, at Washington University and the Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, will be responsible for analysing patients’ DNA.

“Testing has become so easy that we don’t even need to do a blood draw,” Bierut said. “With saliva samples, we can analyze a woman’s DNA and take a look at known genetic variants that contribute to breast cancer. We also expect to find other, previously unidentified genetic variants specific to African-American populations. Our main goal is to improve diagnosis and treatment for these women.”

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is also initiating a research study to examine how biological and genetic factors contribute to the risk of developing breast cancer in African-American women. These researchers will compare the genomes of African-Americans with breast cancer and without the disease, and those of Caucasians with breast cancer. This research will share data, specimens, and resources generated in 18 earlier studies.